Researchers pilot 'itty bitty' device for earlier ovarian cancer detection

As an initial step to creating impact for patients, BIO5 Institute Director Jennifer Barton has worked with TLA to file 3 patents for the invention

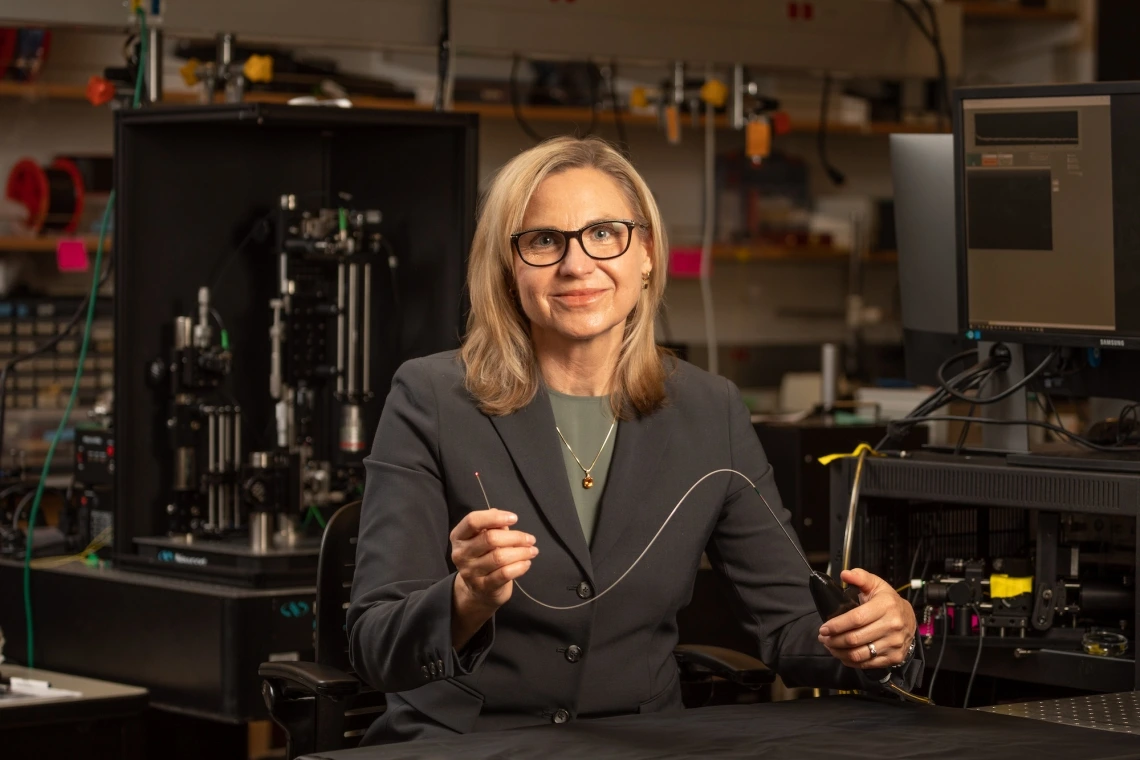

Jennifer Barton, director of the University of Arizona BIO5 Institute and Thomas R. Brown Distinguished Chair in Biomedical Engineering, has spent years developing a device small enough to image the fallopian tubes.

Chris Richards/University of Arizona

Due to a lack of effective screening and diagnostic tools, more than three-fourths of ovarian cancer cases are not found until the cancer is in an advanced stage. As a result, fewer than half of all women with ovarian cancer survive more than five years after diagnosis.

Jennifer Barton, director of the University of Arizona BIO5 Institute and Thomas R. Brown Distinguished Chair in Biomedical Engineering, has spent years developing a device small enough to image the fallopian tubes – narrow ducts connecting the uterus to the ovaries – and search for signs of early-stage cancer. Dr. John Heusinkveld has now used the new imaging device in study participants for the first time, as part of a pilot human trial.

At 0.8 millimeters in diameter, the falloposcope's small size and high resolution are unprecedented. The work to develop a clinical translation of the device has been funded by the U.S. Army since 2018. Barton also is working with Tech Launch Arizona, the UArizona office that commercializes inventions stemming from university research, on strategies to eventually bring it to the marketplace. TLA has filed three patents for technologies behind the device.

"It's itty bitty," said Barton, who also holds appointments in optical sciences and medical imaging, and is a member of the UArizona Cancer Center. "You just couldn't have fabricated something like this, even six, seven years ago."

The American Cancer Society estimates that, in 2022, about 19,880 women in the United States will receive a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, and about 12,810 will die from the disease. Barton hopes her falloposcope will help save the lives of some women and vastly improve quality of life for others.

The falloposcope's effectiveness stems from a combination of multiple imaging techniques. Through a method called fluorescence imaging, which measures the way different molecules absorb and emit light, the device examines metabolic and functional changes in tissue. With optical coherence tomography, the device observes structural changes at high resolution. A third technique – white light reflectance imaging – gathers information about tissue based on the way it reflects light.

In the initial study, the research team hopes to image 20 sets of fallopian tubes before removal. As the surgeon, Heusinkveld will provide feedback to the engineering team about how to make the device easier to use and more effective.

"The goal here is to show that we can get into the fallopian tubes – which is nontrivial itself – take images, assess the quality of the images and get physician feedback," Barton said. "This study will help establish a baseline of the range of what 'normal' looks like."

In the future, with FDA approval, the team's goal is to use the device to image fallopian tubes in patients with a high cancer risk. While it will likely be several years before the device is FDA approved, manufactured and available on the market, this milestone represents a critical step forward in a process that has been over a decade in the making – and could ultimately change ovarian cancer screening protocols forever.

Get the Full Story

This story was adapted from the original content by Emily Dieckman, College of Engineering. Check it out on the UA News website.